« Confirmation bias in science | Main | Top Secret America and the National Surveillance State »

July 18, 2010

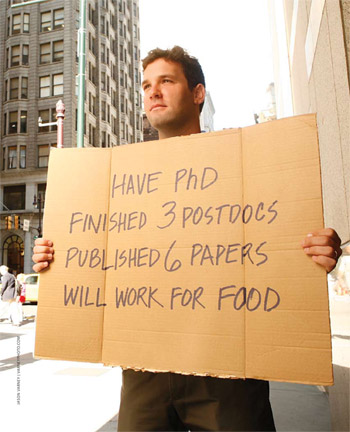

Academic job market

This image popped up as a joke in a talk I saw recently at Stanford, and it generated snide remarks like "3 postdocs and only 6 papers? No wonder he's desperate" and "He must be a physicist" [1].

But, from the gossip I hear at conferences and workshops, the overall academic job market does seem to be this bad. Last year, I heard of universities canceling their faculty searches (sometimes after receiving submissions), and very well qualified candidates coming up empty handed after sending out dozens of applications [2]. I've heard much less noise this year (probably partly because I'm not on the job market), but everyone's expectation still seems to be that faculty hiring will remain relatively flat for this year and next. This seems sure to hurt young scholars the most, as there are only three ways to exit the purgatory of postdoctoral fellowships while continuing to do research: get a faculty job, switch into a non-tenure-track position ("staff researcher", "adjunct faculty", etc.), or quit academia.

Among all scientists, computer scientists may have the best options for returning to academia after spending time in industry (it's a frequent strategy, particularly among systems and machine learning people), followed perhaps by statisticians, since the alignment of academic research and industrial practice can be pretty high for them. Other folks, particularly theoreticians of most breeds, probably have a harder time with this leave-and-come-back strategy. The non-tenure-track options seem fraught with danger. At least, my elders have consistently warned me that only a very very small fraction of scientists return to active research in a tenure-track position after sullying their resumes with such a position [3].

The expectation among most academics seems to be that with fewer faculty jobs available, more postdocs may elect to stay in purgatory, which will increase the competition for the few faculty jobs that do exist over the next several years. The potential upside for universities is that lower-tier places will be able to recruit more highly qualified candidates than usual. But, I think there's a potential downside, too: some of the absolute best candidates may not wait around for decent opportunities to open up, and this may ultimately decrease the overall quality of the pool. I suppose we'll have to wait until the historians can sort things out after-the-fact before we know which, or how much of both, of these will actually happen. In the mean time, I've very thankful that I have a good faculty job to move into.

Update 20 July 2010: The New York Times today ran a series of six short perspective pieces on the institution of tenure (and the long and steady decline in the fraction of tenured professors). These seem to have been stimulated by a piece in the Chronicle of Higher Education on the "death" of tenure, which argues that only about a quarter of people teaching in higher education have some kind of tenure. It also argues that the fierce competition for tenure-track jobs discourages many very good scholars from pursuing an academic career. Such claims seems difficult to validate objectively, but they do seem to ring true in many ways.

-----

[1] In searching for the original image on the Web, I learned that it was apparently produced as part of an art photo shoot and the gent holding the sign is one Kevin Duffy, at the time a regional manager at the pharma giant Astra Zeneca and thus probably not in need of gainful employment.

[2] I also heard of highly qualified candidates landing good jobs at good places, so it wasn't doom and gloom for everyone.

[3] The fact that this is even an issue, I think, points to how pathologically narrow-minded academics can be in how we evaluate the "quality" of candidates. That is, we use all sorts of inaccurate proxies to estimate how "good" a candidate is, things like which journals they publish in, their citation counts, which school they went to, where they've worked, who wrote their letters of recommendation, whether they've stayed on the graduate school-postdoc-faculty job trajectory, etc. All of these are social indicators and thus they're merely indirect measures of how good a research a candidate actually is. The bad news is that they can, and often are, gamed and manipulated, making them not just noisy indicators but also potentially highly biased.

The real problem is twofold. First, there's simply not enough time to actually review the quality of every candidate's body of work. And second, science is so large and diverse that even if there were enough time, it's not clear that the people tasked with selecting the best candidate would be qualified to accurately judge the quality of each candidate's work. This latter problem is particularly nasty in the context of candidates who do interdisciplinary work.

posted July 18, 2010 10:13 AM in Simply Academic | permalink

Comments

I won't quote the stats because I won't get them right (but they can be found on the American Mathematical Society's website if one digs hard enough), but for math there was a big downturn in year 1 of credit crunch (including searches being cancelled, etc.) and then a smaller second downturn the next year even with a supposedly better economy---and I have heard lots of buzz that people left on the market from year 1 was a big reason for year 2. One thing some people have done is stay as a grad student for an extra year even after being ready to finish to hopefully ride things out. And, yes, the overall quality pool will likely end up being diluted as some people who might stay in academia leave (and likely never return). Also, presumably some people who might stay in academia will just be so discouraged by the whole thing (more than the usual numbers) and never both to stay in the first place. The very top people are still getting offers, but after that not so much...

There's another effect that my former postdoc advisor told me about that you didn't mention. Namely, some schools might think they have a chance to get somebody better than they normally would. So in a tight financial climate they are able to offer a job if they get that person but *not* for some "lower" person. In the latter case, the position that is advertised won't be available in practice except for somebody who doesn't need it.

For the purpose of the above comments, I am ignoring the issues with judging which candidates are "better" in the first place. And interdisciplinary people can definitely get hit very hard. I *think* (you'll know more than I do) that networks people are relatively accepted in CS. In math and physics, many of us who spend some time with networks got hired because of research in *other* areas we do. (I know that I was not hired as a networks person, though my other work also is between disciplines---just in a manner that's been around a bit longer.)

Posted by: Mason Porter at July 18, 2010 04:31 PM

You say, "...computer scientists may have the best options for returning to academia after spending time in industry". That wasn't my experience: the scoring formulae used by grant agencies (NSERC in Canada, NSF in the US) are built around the assumption that applicants have been full-time academics for more or less their whole careers. A 40-year-old with only a couple of peer-reviewed academic publications has little chance of getting money (I was turned down five times out of five over three and a half years, compared to a 75% success rate raising money while in industry).

Posted by: Greg Wilson at July 18, 2010 05:18 PM